Tears of American former POW as he returns to Hoa Lo prison

The four-month exhibition is hosted by Hoa Lo Prison Management Board to celebrate 45th anniversary of Vietnam’s Epic Dien Bien Phu in the Air (December 1972-2017).

Army non-commissioned officer Robert P. Chenoweth joined the Vietnam war in January 1967. His aircraft was shot down in Vietnam’s central province of Quang Tri in February 1968. He was then arrested and detained in Hoa Lo prison in Hanoi, which was known to its American inmates as “the Hanoi Hilton” at that time. During his time of imprisonment, Robert gradually got to know more about the war that he was participating in, and thereby he sparked protest against the war through reports, statements, and meetings with international peace groups during their visits to Hoa Lo.

Robert shared that his military career truly began when he “became a guest of Hoa Lo”, where he and other prisoners could learn painting and playing musical instruments and explore Vietnamese culture through English books published in Vietnam at that time.

“Five years in the prison, I read English books on Vietnam such as "Vietnam Today” and “Vietnamese Studies” by culturists Nguyen Khac Vien and Huu Ngoc,” Robert recalled. “We also discussed in groups, which gradually helped inspiring my passion for Vietnamese culture and history,” he added.

Being moved to Hoa Lo prison at the time of the US Christmas bombing in 1972, Robert and other prisoners established a 10-member group named ‘Peace Movement”. “We once wanted to send a letter to the US Congress to stress the significance to withdraw US soldiers back home, but our request was not approved by the prison’s management board as they were afraid that our letter would be misunderstood by the Government that we had been brainwashed.”

“I lived here 45 years ago, and experienced historic events including the Dien Bien Phu in the Air and the signing of the Paris Agreement,” Robert said.

“My stay in Hoa Lo began in the midst of the nightly B-52 attacks. Everyone was worried about the damage happening around us and we hoped for the safety of the families of all the camp cadres. During this dangerous time, the guards and interpreters asked me if I would like to take home a small tea set. I was grateful for this gesture of kindness.

Robert left Vietnam on March 15, 1973. He still keeps the tea set at his home today. “Perhaps on another visit, I’ll bring it back to give to the museum," said Chenoweth.

The former P.O.W. presented 12 memorabilia to Hoa Lo prison, which included daily items he used in prison, such as clothes, towels, bowls and chopsticks. Chenoweth also gave the flag of Vietnam, which was a gift from Colonel Tran Trong Duyet, former prison warden, to him on the day Robert left Vietnam.

“The flag became a powerful symbol of the period of time I had stayed in Hoa Lo and Vietnam as well as all the things I had learned during my captivity. It reminded me of the long struggle of Vietnam to protect its independence,” said Chenoweth.

Recalling the olden memories, Robert couldn’t stop his tears, and he had to take a long pause to return to his story. Crying interrupted sentences, he said he had a mixture of feelings when he returned to the prison for a visit after 45 years.

He was also glad to see the former prison warden Tran Trong Duyet again, who had changed Robert’s thoughts on the war and helped him learn more about the meaning of peace and Vietnam’s struggle for peace as well as the life of Hanoians during the bombings.

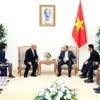

Tran Trong Duyet, who was also present at the opening of the exhibition, happily shook hands with Robert, and the two men then looked at the old picture and reviewed past memories.

“He taught me English at that time,” Duyet recalled. Describing young Robert, Duyet said “He was good-looking, tall and wore glasses.”

Talking about the reason why he presented a Vietnam flag to Robert, Duyet said it was because Robert showed a lot of sympathy for Vietnam, and he believed that the red flag with the yellow star would convey a meaning of justice to Robert.

In reply to a question about his work at that time, Duyet said that he was tasked with ensuring health and safety for the prisoners so that the 500 prisoners could be the key for Vietnam in negotiations. The prisoners were served with meals which were event better than Vietnamese colonels, Duyet revealed.

In a reminiscent mood, Duyet said that he was also the prison warden of US then Senator John McCain, and Peter Peterson, who then became the first US Ambassador to Vietnam (1997-2001). McCain taught me to speak some English during the weekend, and we often chat with each other like two ordinary men on a lot of things, including flirting with girls.

During wartime, the US soldiers were conducting bombing raids on the Vietnamese people, but in peacetime today, they are our friends who have played an important role in bolstering the normalisation of bilateral relations between the two countries, Duyet stressed.

Reuniting after 45 years, the prison and his warden shook their hands, gave a tight hug for each other, and exchanged sincere wishes for each other. Although they once fought against each other on opposite battle lines in the past, there is no distance between the two old men at the present.

With more than 250 items, ‘Finding Memories’ exhibition takes people back to the tough 12 days and nights in late December, 1972 during the US Christmas bombing of Hanoi.

‘Finding Memories’ recreates the struggle of local people who overcame the sorrow and loss caused by the war. It also gives visitors an opportunity to understand the severe destruction and painfully grim nature of war.

The exhibition will last until March, 2018 at Hoa Lo Prison Historical Relic Site, Hoa Lo street, Hoan Kiem district, Hanoi.